By Paulina Hernández / phernandezj@udec.cl

/ Photographs: Fulgencio Lisón

A zoonosis is a disease that manifests in the human population as a result of a pathogen commonly present in domestic or wild animals. Most diseases are enzootic, meaning that they remain stable within populations of wild animals.

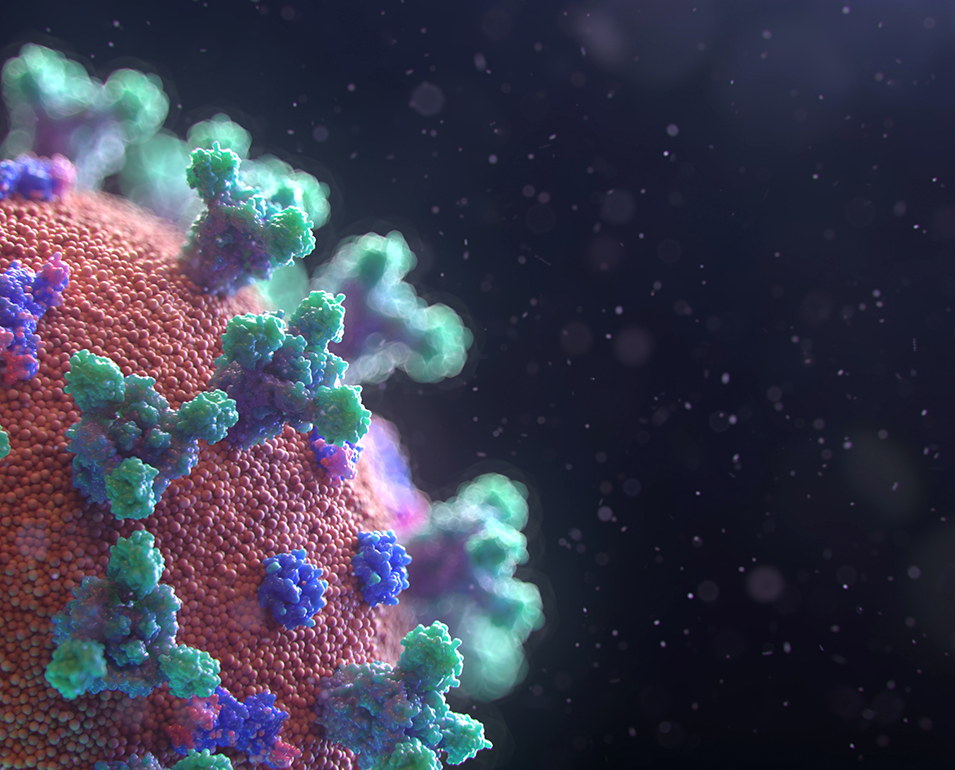

The coronaviruses are diverse group of viruses present in mammals. Currently, close to seven coronaviruses can infect the human population. Of these, only three cause severe diseases: SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2.

“To understand the potential zoonotic origin of this virus, we must first understand how the virus communicates with and then infects human cells. This is done through a spike, a structure on the viral surface. The spike of SARS-CoV-2 has two relevant traits: 1) a site to bind with the human cell, and 2) another site that makes it pathogenic,” explains Dr. Enrique Rodríguez, researcher for the Department of Zoology of the Faculty of Natural and Oceanographic Sciences and Director of the Mammalogy Lab.

“According to a recent study, SARS-CoV-2 presents 96% genetic similarity with the coronavirus of the bat Rhinolophus affinis and a little less similarity with the coronavirus of the Malaysian pangolin Manis javanica. Notably, the pangolin coronavirus can bind to human cells. Therefore, it is highly probably that the ancestral form of the virus that is today infecting the human population of the world is from the pangolin,” adds Dr. Rodríguez.

However, Dr. Rodríguez further explains that to become SARS-CoV-2, the original virus underwent a strong process of natural selection in the organisms of the first people infected. This included adaptations conferring pathogenicity in humans, cats, ferrets, and other species. This “imperfect” adaptation is strong evidence for ruling out any artificial origin.

This is how the zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2 can be confirmed. Nevertheless, the virus is not a zoonosis as such due to being markedly different from the ancestral species that infects pangolins, i.e. the final form of the virus developed in the initially infected human population.

For Dr. Fulgencio Lisón, researcher for the Department of Zoology and Director of the Laboratory on the Ecology and Conservation of Wild Fauna, coronaviruses have formed part of bat fauna for a long time, and the incidence of coronaviruses in bats is low (i.e. less than 7% of captured bats have coronavirus).

“The same study reported that while the current COVID-19 has similarities with only one species of bat (R. affinis), it hardly matches any other coronavirus in bats. Some researchers suggest that the virus passed through bats as an intermediate hots, where it recombined with other coronaviruses (the viral spine is very similar to pangolins, but is not at all like bats) and a hybrid arose, which is SARS-CoV-2.”

In 2007, a report established that south China could have an epidemic outbreak of severe respiratory syndrome caused by coronavirus due to the capture and consumption of wild animals. Since the mid-20th century, we have likewise clearly understood that changes to ecosystems have significant consequences on the density and behavior of wild animals, which can mean more interactions with the human population. “Faced with this background, the current pandemic cannot be explained in any other way except through the deep-rooted negligence of the ruling parties of the most powerful nations and, by extension, negligence in not using the available scientific knowledge to implement evidence-based policies that could curb self-destructive human behaviors. Consequently, research that aims to predict events like this health crisis should be financed and encouraged. Additionally, extensive changes should be made to current policies as related to intervening in natural systems,” states Dr. Enrique Rodríguez.

More information:

Dr. Enrique Rodriguez Serrano, enrodriguez@udec.cl;

Dr. Fulgencio Lisón Gil, flison@udec.cl